You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Philosophy’ category.

This will probably be a short post (well see). Mainly, I wanted to point out why I think we read this chapter from Carroll. In short, we read this to give us an example that designing for affect, particularly humor or horror, is possible. Not only is it possible, Carroll lays out some of the mechanisms by which we experience this emotions and feelings. We have been talking a lot in class about individuality and connectedness between audience, designer, user, person. What Carroll’s account of horror and humor does is give us evidence that people respond to certain stimuli in very similar ways.

Carroll’s notion that we find a monster repulsive , impure, or threatening (Carroll’s necessary condition for a movie to be of the horror genre) is a recognition that we all, for the most part, agree what is repulsive, impure, or threatening. This suggests, strongly, that we are so constituted that there are simply uniting dispositions that allow us to experience horror and humor together. There is a commonality among our perceptions, understandings, and affect that allow for our shared reactions to horror or humor. For design, this means that we can, sincerely, design for certain affects — and it works. The evidence of centuries of storytelling that have successfully engendered these emotions and feelings and audiences is enough evidence for us to move forward with this idea in our HCI work.

But, there are certain questions we must ask as we move forward. Literature and film are two different mediums though which humor and horror are achieved, UX design is a third. What are the cues, styles, stimuli of UX design so far as they can engender horror or humor? Are these different from film or literature, are they the same? How will we develop our language of affect for UX design? Has it already been developed? Are there formal criteria by which we must measure our UX design?

This post will largely be about the role of intention in Design, whether on the part of the author, critic, or audience. More, the notion of intention is necessarily relied to the meaning making that occurs when participating in design in any of the three roles (designer, critic, audience). Because design’s project is about proposing a new world, a world found to be new by the rethinking of moral systems, emotional responses to stimuli and greater emotional capacities, or the Beautiful, no one person or group of people can provide an argument that hinges upon truth value. Rather, design aims for the plausible, the new, the better, or the unexamined. If design’s project was similar to finding the hardest rock in a box full of rocks, agency and truth value would not be contentious. It is because design wrestles with the fundamental questions of what it is to be a person in this world, that design cannot obey truth value. In this way, design escapes (as Jeff said) the attraction of demonstrating some objective truth, but rather supplies a plausible interpretation of what it is to be human or how life can be lived.

“Design, too, is far more about changing the world than representing it, though certainly it makes heavy use of knowledge representations (e.g., market data, user studies, and social science) to do so.” (p.619)

If Design is said to be about future-making, in the quote as “changing the world”, then design’s main project begs an important question: what, if anything, can we really know about the future? That is, what can we say we know, here engaging Knowledge in a philosophical tradition, about the future. The conditions under which we subscribe something to knowledge don’t exist for future-thinking. At best, all we have for the future are predictions or fantasies we create. This idea is encapsulated by David Hume:

“That the sun will not rise tomorrow is no less intelligible a proposition and implies no more contradiction than the affirmation that it will rise.” – David Hume

Because future-building is the project of design, there is a certain sense of arrogance in the intentions of a critic or designer, if these intentions are characterized by only their truth value.

“Criticism, as I argued earlier, is committed to raising our perceptual ability, our ability to notice and make sense of the relationships between the formal and material particulars of cultural artifacts and their broader socio-cultural significance. ” (p.619)

Here the notion of audience agency is central. All of us, together, have an operator’s role in the meaning making of our future worlds. I forget which author said this but its the idea that we all create mini-Utopias rather than obey some authoritative notion of a utopian world. But this only works if we restrict Criticism to the role of finding value in relation to future-building. In this way, Criticism can improve our perceptual abilities — here making it a possibility for audiences to supply their own perspective on topics of moral systems, the Beautiful, emotional capacities, and other parts of life that have successfully evaded truthful definition for millennia. When it comes down to it, making a normative claim about any of these things limits the agency of audience (users for HCI).

Now, there are limitations to this. I am not saying intentions are valueless. Indeed artistic or designerly intention is vital to understanding a horror film as something enjoyable rather than a seriously disturbed perspective on the way life should be.

Many ideas came to my mind today at class… Here there are two of them.

* I think that art might be a form of control… how can the artist create art that really leverages society? It you’re educated on criticism and to do critique, you may get critical about your role as a designer and about your work… Therefore, you won’t be able to ignore the degree of “commodified dreams” that your work might represent, your work environment might represent, and your work context (micro-world/business world) might represent.

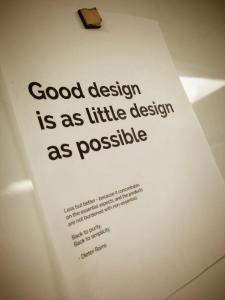

* When students start learning about design, they go easily à la “Dieter Rams” way. I believe that as “older” as you get, and as better “knower” as you get (regarding Design), you may observe that design is a) richer and b) there’s no right or wrong design.

I am going to tie Carroll’s reading and his account of criticism in with my capstone project for this post. My capstone project is an investigation into Problem Framing as part of the process of designing. Currently, I am analyzing, and yes critiquing, different HCI domains like Ubicomp, mobile, HCI4d, and Critical design to try to suss out how academics who publish in this area go about their problem framing. Namely, I want to try to connect the process of problem framing with Carroll’s account of criticism as an activity that exposes value to an audience.

So far I have noticed trends in Problem Framing like relying on expert opinions in certain domains, designing for particular demographics by following specialized constraints and assumptions, and, overall, the focusing on exposing the true nature and subtleties of some affliction people are experiencing. In short, seemingly most of the design processes I read can be characterized by designers who identify some pain point, inequality, or lack of comfort X (taken from some other demographic or culture) and then try to solve for these ‘situations’.

These designers try then to design for these ‘situations’ by a similar process Carroll laid out in his first chapter namely the description, elucidation, contextualization, classification, interpretation, and/or analysis of the situation so as to lead to insights as how to solve the ‘situation’ or problem. Where I think there can be a contribution made to Problem Framing is that, instead of being problem-focused, what if designers focused on using Critical Evaluation to find value in certain “situations” and to then use their power of criticism to foster new understandings and manifestations of this value in terms of designs.

I understand Carroll’s account of criticism to be the following: “…criticism is primarily committed to the discovery and illumination of what is valuable in artworks.” (p.46) More, this type of evaluations is based on reason. Carroll goes on to explain that the other activities involved in producing a critique are hierarchically subservient to evaluation, that is they play a special role in providing good reasons and justifications by which the evaluation can be made. Carroll’s main contribution is fore-fronting the importance of evaluation as part of the critique process. Indeed, Carroll claims that the evaluation is the end product of criticism in that “criticism is strong criticism insofar as it renders its evaluation intelligible to audiences in such a way that they are guided to the discovery of value on their own.” (p.45) If I am planning on using this framework as something, in someway, is related to problem framing I need to answer a few questions that came up while I was reading Carroll.

First, what type of evaluation, as the primary activity of critique, would be appropriate for trying to understand problem framing? Carroll gives a few accounts of evaluation: political, ideological, artistic, negative, or positive. Each one of these types of evaluation has different motivations. Carroll talks about motivations for evaluation in his discussion of the ‘lack-of-general-criteria’ argument. In that, without general criteria by which an evaluation of an artwork could occur, “something else” must take the place of reason as a basis for evaluation.

“Historically, some of the leading candidates for that “something else” have been emotion, subjectivity, or political motivations (either politics in the large sense, as in the case of classism, racism, or sexism, or politics in the sense of interpersonal power relationships).” (p.30)

Earlier in the introduction Carroll identifies the outcomes of some of these candidates in that they “frequently pave the way for negative evaluations of candidates in terms of sexism, classism, logo-centrism, etc.” (p.5) What struck me with this characterization is the admittance that evaluating in these terms often produces negative evaluations. “This design is too Western” “This design is patriarchal” “This design inflates the capitalistic ideal” are all examples of the negative type of evaluation designs can received when evaluated using any of the candidate motivations laid out by Carroll. While these evaluations are important, and often apt, they firmly voice problem framing in terms of the current status quo, even if it is the negation of the status quo. In this way, these candidate motivations for evaluation of design framing excludes alternative future thinking.

Carroll draws a distinction between negative evaluation and something I call “value-finding” evaluation. Carroll sees the project of negative criticism as:

“Indeed, a constant diet of negative criticism–relentlessly pointing our the bad and the ugly in artwork–would be so impoverished that I suspect it could not be sustained for very long. For it is the promise of contact with what is valuable that we ultimately hope for from criticism.” (p.47)

Drawing out the value in design opportunities or spaces rather than characterizing them in negative terms is analogous to Carroll’s account of negative and value-finding evaluation of an artwork. Because evaluative criticism, which is based on reason, can help find value in a design space, it can be supportive of designers who wish to provide for alternative futures the kind of which do not depend on existing problems.

I haven’t fully flushed out the place of reason and its relation to how I want to propose Criticism as a tool for problem framing, but I do want to engage with Carroll’s account that emotions need not compromise critical evaluation. He goes into his account on pages 30 and 31 if you want to check it out, but I offer no summary of his argument other than its ok for some emotional aspect of evaluation to exist in concert with any reasoning aspect. This is paramount for critiquing a design space. Since we design for value and for people, affect is a necessary part of whatever experience we design for. In this way, Carroll’s account of critical evaluation neatly accounts for the type of evaluation needed in design work. More, since Carroll’s account of evaluation hinges upon value-finding and value-illuminating, his type of evaluation maps nicely to the sort of relationship design has with ethical values. In this way, criticism in design can do important work in value-finding and value-illuminating specifically in an ethical realm.

There is a ton more I could write, but as this is already a 1,000 word blog post, and most of you probably wont even get this far I am going to stop. But, I want to make a list of other things that need to be considered:

-The relation between the critic, criticism, and the audience in design criticism. Who are these parties, what is their relation?

-What types of values are to be found for identifying and illuminating in designs?

Recently Jeffrey Bardzell created a blog post entitled, “Roy’s Coca-Cola and Critical Design” and like Andy Warhol, created a Brillo Box, Jeff posed the question could a blog post be art. First, allow me to elaborate, Jeff created a blog post with two interesting perceptual difference between Roy’s earlier blog post, Coca-cola and Critical Design The first change is that in Jeff’s Post he has has changed title adding Roy’s name to the front of it and changing the “c” in cola to a capital letter, and the second – and arguably more interesting – is that Jeff has changed the category from Humor to “This Post Is Itself A Work Of Art“. Danto argued

But that was Warhol’s marvelous question: Why was Brillo Box a work off art when ordinary boxes of Brillo were merely boxes of Brillo?

In a similar way, Jeffrey has called attention to his post, defining it as art and raising the question can a blog post be art and are other blog posts made in this blog art as well?

As Danto argued with Andy Warhol, I will too argue that Jeff’s blog post, “causes reflection on what makes it art, when this will not be something that meets the eye just as the film demonstrates how little is required for something that meets the eye.” Interestingly enough however, Danto argues that,

“Warhol’s way was clearly a via negativia. He did not tell us what art was. But opened the way for those whose business it is to provide positive philosophical theories to last address the subject.”

Finally, I would argue that this is where a difference lies between Andy and Jeff. Unlike Andy, who as Danto argues, did not classify his Brillo Box as art, Jeff clearly has categorized his post as art and this represents another philosophical joke within the context of this blog that is commenting on both Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box and Roy’s Coca-cola and Critical Design. This makes it in a way similar to Brillo Box because it poses these questions to ask the reader.

I really enjoyed the discussion on aesthetics, and the Danto reading really helped to pull it all together. It also made me ponder many things; luckily for you, I only remember a few:

ICT4D

Many moons ago I stared at a blinking cursor (now there’s an aesthetic expression!) desperately praying for some coherent thought to flit by so I could pin it to The Statement of Purpose. One of the not-so-coherent thoughts that kept popping up was something like “ICT4D should be pretty too…because it affects how people engage with it.” So the notion of aesthetics as a matter of ethics hit home as “Bingo; that’s it!”

Aesthetics is to surfaces as body language is to human beings. Very few people merely listen to what you say, and act on that alone. What you say will always be mediated by how you said it. The medium is the message. I wonder now if that isn’t partly why younger people are more likely to blame technology for a failing, while older people are more likely to blame themselves. Apart from having grown up with more technology, they grew up with particular forms of technology – tech you could put in your pocket or customize as a fashion item; or flat, black minimalist PC forms that practically apologize for taking up too much space. Contrast that with the large, standalone, mini-edifices of the older mainframes; or interfaces that required you to talk their language; or PC forms that were white or bright and showy and took pride of place in the household. What conclusions would you draw?

Mr. Bennett

I’m not sure if the timing works out (having to toggle your wi-fi every 30 seconds seriously cuts into Googling rigor) but if Jane Austen was influenced by Wittgenstein, I now really understand what she meant when she described Mr. Bennett (Pride and Prejudice) as a philosopher. It’s one thing to find ironic humor in having an atrociously silly wife and like-minded daughters, but to not do anything about it at all? I mean, she was like the proto – Jar Jar Binks. Now I understand he was actively pursuing non-action, since apparently that’s what philosophers do.

Abstractionist Life? (a.k.a Why the Abstract Expressionists Were Like the Dealers in Sub-Prime Loans)

One of my favorite stories is this pithy parable of the Credit Crisis:

If you don’t have time for pithy parables, the moral of the story is that things went awry because people started selling concepts and concepts of concepts at the expense of the real thing – much like the abstract expressionists did. I guess that technically makes Andy Warhol the Crisis.

Thing is, it’s one thing to abstract to that level in art, but I think we’re doing that, to our loss, with real life. And to illustrate, here’s a video one of my classmates posted of a toddler’s first experience with rain:

Little Girl Experiences Rain for the First Time

(Used here under educational fair use)

As charming as the video is (and shocking to my Jamaican sensibilities – to have your baby play out in the rain? You must be mad!), I couldn’t help but contrast the baby’s first hand engagement with the all the camera phones trained on her. That’s pretty much how we enjoy things these days: through a screen, attempting to capture for posterity a moment we didn’t actually get to experience ourselves – we were so busy recording it.

P.S. I doubt that link on Jar Jar Binks really gives you a true appreciation of the character, but it does allow me to go into a mini side-rant about the “allegations of racial caricature”: Wha? I might need to watch his appearances again (riiiight; I’m not that much of a sucker for punishment), but in this case, I seriously suspect that the fact that people liken him to a “Rastafarian Stepin Fetchit” etc. says more about those people than it does about the character.

In class today I mentioned Testadura, Danto’s imaginary “hard head” who doesn’t understand art at all. If he sees a painting, he just sees a canvas with paint on it.

So the thought experiment is: What would Testadura have to say about Drift Table?

So this is going to be my attempt at summary and explanation of Danto. I seriously doubt that I’ll grab everything (Or even much more than a solid hand(head?)ful), but hopefully we can talk more directly about some of the points that are made. Overall I found it to be a fascinating, and yet easy read – probably as Jeff points out to my detriment as I likely missed some of the deeper implications he’s trying to make.

Let’s start at the very end though, because I think it pretty well sums up his argument, and gives a bit of a map as to where the pieces of the argument are:

He turned the world we share into art, and turned himself into part of that world, and because we are the images we hold in common with everyone else, he became part of us. So he might have said: if you want to know who Andy Warhol is, look within. Or, for that matter, look without. You, I, the world we share are all of a piece.

It’s kind of hard to see exactly what he means here without the context of the rest of the piece, but basically I see Danto as arguing that Warhol directly challenged and changed the way we think of art, and brought it to a much wider and more every-day context, much the same way Dewey (as Angelica points out! Great insight!) for experience.

In fact, Danto’s main argument almost has a similar structure to Folkmann’s (This is tenuous… perhaps I should have left it out?):

He turned the world we share into art

This is the Sensual – phenomenological part, where Danto explains that Warhol’s exploration of art of everyday objects simultaneously brings with it a re-valuing of the everday of art. This is seen directly through Danto’s exploration of what Warhol is doing with form, shape, and medium (sensual characteristics), such as in Brillo Box, or Empire. And on this level, I believe is Danto’s point (Or Warhol’s. Are they different?) – If an everday object can be art, isn’t art an everday thing?

and turned himself into part of that world

This would be Folkmann’s Conceptual- Hermeneutical -This I think deals with the more meta-art aspects of Warhol’s work, him versus the ideas of art, or him versus abstract expressionism’s “self-proclaimed heroism.” Ideas like:

“Nothing could be deeper or more meaningful than the objects that surround us, which are “more numerous, more sound, and more subtle” than all the portentous symbols dredged up in sessions of Jungian analysis, about which ordinary people know nothing and regarding which artists may be deluding themselves in supposing they know more.”

Finally, we have the last aspect:

and because we are the images we hold in common with everyone else, he became part of us.

And finally this is the Contextual – Discursive. This is where Danto talks about Warhol’s work of symbols and character. Icons. Marilyn Monroe or Warhol himself (Was his life character art?).This is the contextual, social, political ideas wrapped up in everything we do:

Warhol’s art gave objectivity to the common cultural mind. To participate in that mind is to know, immediately, the meaning and identity of certain images: to know, without having to ask, who are Marilyn and Elvis, Liz and Jackie, Campbell’s soup and Brillo, or today, after Warhol’s death, Madonna and Bart Simpson. To have to ask who these images belong to is to declare one’s distance from the culture.

And of course the three levels of Folkmann’s Aesthetics apply and are connected throughout, but taken as a whole these basic ideas that Warhol played with introduce much more than, I think, simply ‘all things can be seen as art’

He did not tell us what art was. But he opened the way for those whose business it is to provide positive philosophical theories to at last address the subject.

Philosophical understanding begins when it is appreciated that no observable properties need distinguish reality from art at all. And this was something Warhol at last demonstrated.

It’s not only just ‘all objects can be seen as art’. But everything – ideas, people, lives, values, and importantly the cultural and social connections we make between all these things. The object is art, but so is the viewer, and the dialogue between them. As far as I can tell, Danto’s reading of Warhol is some sort of awesome *real world example* of the Deweyan or Folkmann understandings of aesthetics and experience which we’ve been arguing about for some time.

Many of us have said “yeah that’s interesting, but how is that applicable?” – myself included. Warhol was someone who really applied it.

“Nothing could be deeper or more meaningful than the objects that surround us, what are “more numerous, more sound, and more subtle” than all the portentous symbols dredged up in sessions of Jungian analysis, about which ordinary people know nothing and regarding which artists may be deluding themselves in supposing they know more.” (Danto, p.79)

That quote comes at a point in the reading where Danto is describing the historical context, both in art and philosophy, surrounding the creation and publication of the Brillo Box. The abstract impressionism movement promoted a rejection of the daily culture in preference for a connection with the subconscious and primal expressions of humans. Pop art, in Warhol’s words “is about liking things” (p.74) The philosophical community was having a similar debate when it came to language and what kind of language we should be using to describe things, along with demoting the importance of common sense and “ordinary language”. Yet J.L Austin (Oxford Philosopher) makes a remark similar to what Danto says in the quote at the top of this post, and similar to the Pop art movement, saying:

“Our common stock of words embodies all the distinctions men have found worth drawing, and the connexions they have found worth making, in the lifetimes of many generations: these are surely likely to be more numerous, more sound, since they have stood up to the long test of the survival of the fittest, and more subtle, at least in all ordinary and reasonably practical matters, than any that you or I are likely to think up in our arm-chairs of an afternoon.” (p.78)

What this means to me, and in connection with the top quote, is that everyone, together, as an active role in the meaning making of how we interpret, interact, or perceive the world. Our objects we make are like the words we create to draw ‘distinctions and connexions’ with the world around us. Because of this, no artist, philosopher, or psychologist can tell us what is art, what is a well-designed object, or what language is truly appropriate for certain spheres.

This impacts my understanding of HCI design because we make digital objects. But like the artists, philosophers, and psychologist who cant tell us what to think, we can’t tell our users what a well-designed digital object is. This idea means a greater responsibility not to create dull, temporarily useful, objects that take up time in our daily lives and add little to them. But rather to approach designing objects, perhaps as ‘meaningless’ as another app or website, as you would creating a new word that will be added to the dialogue of humanity, perhaps standing the test of time.

My capstone project is about problem framing, and its relation to design or the design process, and reading Danto’s piece made me think about framing in a different way. If I think about an object like I would a word or piece of language, then there should be a clear reason for it to exist. While I can armchair my way through hundreds, maybe even thousands of potential new words (objects), this is in now way an effort equaling “all the distinctions men have found worth drawing, and the connexions they have found worth making, in the lifetimes of many generations” (p.78) THis gives me a new analogy to work with when trying to understand the link between problem framing and the design process. I think critical design can work in some ways like the Brillo box in that, while the Brillo box served to challenge nearly everything we understood art to be, critical design can serve to challenge designs as they solve a problem. Critical design can then challenge not only some finished design, but the problem framing and perhaps even the process itself.

I also think that this highlights the mandatory inclusion of outside perspectives in the design process, beginning with framing. We cannot sit in a room and think of the problems that exists in the world. At best, these problems will be cursory, much different from the complex, real problems that need actual solving. In understanding problem framing, I think this can be used to explain some of the problems of assumptions in the framing of problems, as well as bias in its many forms.

“‘Aesthetic delectation is the enemy to be defeated,’ Duchamp has said in connection with this genre of work, and the readymades, according to him, were selected precisely for their lack of visual interest.” Danto, page 72, PDF page 12.

But if the choice of objects was founded on their “lack of visual interest”, Duchamp is acknowledging their are also objects that are visually interesting. More simply put, if it’s possible to have a lack of something then it’s also possible to have an abundance of that same something. For Duchamp, that something is visual interest.

By admitting that some objects of aesthetic consideration are, in fact, beautiful, isn’t Duchamp giving validity and form to the extant framework of aesthetic delectation?

Have Duchamp, and subsequently Warhol, shot themselves in their collective philosophical foot?

Recent Comments